ASHLEY SNOW, JR.

Aviation Chief Machinist Mate, USN

Chief Pilot

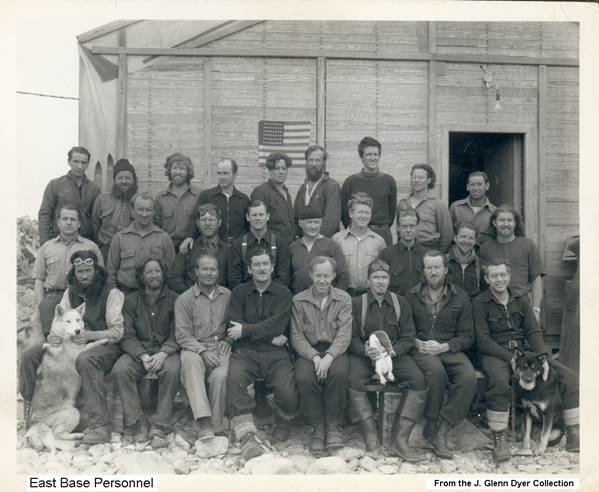

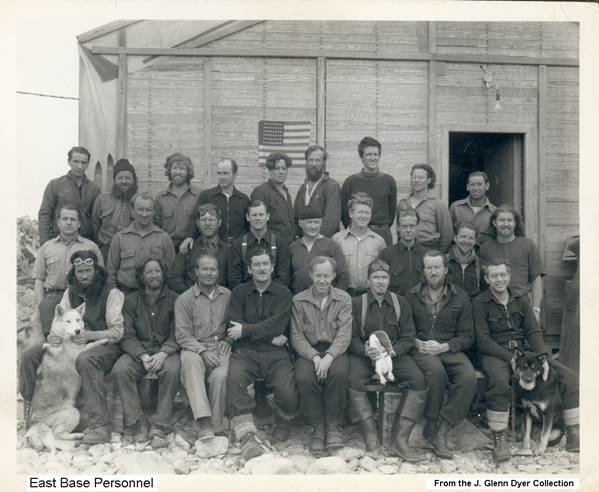

East Base

Biography:

by

Laura Granberry

Snow

My father, Ashley Clinton Snow, Jr., was born March 23,

1906, in Meridian, Mississippi, to Laura Granberry

Snow and Ashley Clinton Snow, Sr.† He

attended Marion Military Institute, Marion,

Alabama, from the first grade

through completion of his first year of college.†† His father was a lumberman by trade and

traveled throughout the country and Latin America

purchasing timber.† His mother, a native

of Meridian, Mississippi, was a southern beauty and

gifted singer who was invited to sing in churches throughout the South.† My grandmother was the author of Music and the Out

of Doors, published in 1930, by the Museum

of Natural History in New York City.†

Joining the Navy in 1927, my father was accepted into flight

school in 1929, and received his wings in 1930.

In 1939, he applied to the United States Antarctic Service to be a pilot

and was accepted.† The two expedition

ships, the USS Bear and the USMS North Star sailed for Antarctica in November 1939.††† My father was pleased to be assigned to the

historic USS Bear, a three-masted barquentine built in Scotland in

1872.†† The Bear was under full sail for

weeks and because they were not traveling in commercial shipping lanes they did

not see other ships or inhabited islands for extended periods of time.† The newly installed diesel engines were used

only when the ship got into the pack ice.

Life on the Bear was spartan, but it was an extraordinary experience that my

father never forgot.

Four aircraft were utilized during the expedition.† Two aircraft, a Beechcraft

and a Curtiss-Condor were assigned to West Base.† Only one aircraft, a Curtiss-Condor, was

assigned to East Base.† The Bear carried a Barkley-Grow

that was on loan from a private individual but returned to the United States

with Admiral Byrd.† The Barkley-Grow had

a longer range than the other expedition aircraft and was therefore more

suitable for the flights of exploration planned by Admiral Byrd.† The fact that East Base was provided with

only one aircraft resulted in a precarious situation for that base.†

The first stop in Antarctica was Little

America where West Base was constructed.†† As the USMS

North Star unloaded, it was Admiral Byrdís plan to take the Bear and explore the region.† Paul Siple, West

Base leader, and Richard Black, East Base leader, were concerned about the Bear leaving on an exploratory

voyage.† Admiral Byrd apparently advised

no one about his destination or plans.

With my father as pilot, Earle Perce as copilot, and Admiral Byrd as

navigator, they flew over 100,000 square miles of territory, discovering

mountains and islands, and added 700 miles of coastline to mapped territory.

These exploratory flights were particularly dangerous because they flew over

heavy broken pack ice in uncharted areas.

Unfortunately, there was no aerial film footage taken on these flights.†

After the construction of West Base was well on its way to

completion, and the Snowcruiser, Beechcraft,

and a Curtiss-Condor had been offloaded at West Base, the Bear sailed for Marguerite

Bay, adjacent to the Antarctic

Peninsula.† The North Star sailed for Valparaiso, Chile.†† The Curtiss-Condor intended for East Base had

been stored in Valparaiso

under the watchful eyes of William Pullen, along with the prefabricated housing

panels for the main bunk house, for which Robert Palmer had been

responsible.† The North Star sailed to East Base with the housing panels and the Condor.† Immediately after all East Base materials had

been offloaded, the Bear and the North Star had to depart because they

were in danger of being iced-in.† Until

their housing was complete, the ice party lived in tents.

When the Curtiss Condor was shipped from the United States,

the wings were removed and placed into a huge crate.† After assembling the aircraft, the aircraft

crew adapted the huge wing crate into an ďaviation shack.Ē†† The aviation field was a mile from Stonington Island, the location of East Base, on a

glacier connected to the island by a thick slope of snow.††† The dismantled crate was moved to the

glacier, rebuilt, and covered with a thick tarp.† Four bunk beds and a work bench were built,

and a pot-belly stove was installed.

Because of the difficult and quickly changing weather conditions in the

Marguerite Bay area of the Antarctic Peninsula, it was necessary for two men to

remain close to the Condor at all times.

My father and William Pullen lived in the aviation shack.† Earle Perce was scheduled for regular radio

duty and spent long periods of time at the main camp when he was not flying or

working on the Condor.†††

Flying duties included reconnaissance flights to find the

best sledging routes for the trail parties, cache-laying flights, and

photographic flights in which Art Carroll documented the geography of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Flights were made in order to deliver photographs to trail parties to

assist them in locating the best routes to their destinations.† My father and Earle Perce depended upon

Herbert Dorsey, Jr.ís weather forecasts in order to

undertake these flights.†

The original mission of the United States Antarctic Service

was to establish two permanent bases where personnel would live and operate for

a year until they were relieved by the next group.† These plans were cut short due to concerns

about Japanese activity in the Pacific and the belief that the United States

might enter the war.† The Bear and the North Star returned to Antarctica

in 1941, evacuated West Base and subsequently sailed to East Base.† The situation at East Base proved to be

difficult because the ships could not get close to Stonington

Island because Marguerite Bay

was filled with pack ice.† In

mid-February both ships were still in the vicinity of Stonington Island,

awaiting a change in wind direction that would clear the ice.† On March 15, the North Star sailed to Puntas Arenas, Chile, in order

to allow the West Base personnel to disembark.

Supplies were picked up in case East Base personnel had to remain for

another year.† The Bear sailed to Mikkelsen

Island (currently named Watkins Island) and personnel established a

landing field on top of the island, 400 feet above. In Washington, Admiral Byrd and the Executive

Committee of USASE gave Captain Cruzen of the Bear permission to make the decision

regarding any possible evacuation.†

On March 21st, Captain Cruzen

gave the order to evacuate East Base the next day.† All East Base personnel volunteered to

evacuate on the second flight.† Every man

knew the Condor had been patched up several times and there was a significant

chance the aircraft might not be able to return to East Base after the first

flight.† Base Leader Richard Black chose

the men for each flight according to the necessity of having them at East Base

for another winter in the event the aircraft did not make it back for the

second group.† The first group of evacuees were:

Darlington, Dyer, Dolleman,

Healy, Hill, Hilton, Morency, Odom, Palmer, Pullen, Sharbonneau, and Steel.

Each man was allowed to take the minimum of possessions with him.†† My father and Earle Perce took off from East

Base at 5:30 a.m., with the twelve passengers aboard the Condor.† The aircraft landed atop Mikkelsen Island at 7:15 a.m.†† The Bearís

radio operator notified East Base of the successful landing.†

The Condor returned to East Base at 10:00 a.m.† By 11:10 a.m., the aircraft was refueled and

the pilots, with Black, Bryant, Carroll, Collier, Dorsey, Eklund,

Knowles, Lamplugh, Lehrke, Musselman, Ronne, and Sims aboard, attempted to take

off.† The aircraft was unable to do so;

therefore, my father ordered the disposal of five hundred pounds of personal

possessions.†† Time was of the essence as

the Bear was becoming encased in

ice.† At 12:15 p.m., the aircraft took

off successfully and landed at Mikkelsen Island

at about 2:00 p.m.

†

Human tragedy was averted as another tragedy occurred.† There were sixty-seven sled dogs that could

not be taken aboard the evacuation flights.

The airfield surface was softening as the temperature warmed.† The aircraft was in dubious condition.

Additional flights were deemed too risky.

The decision had been made the night before that the dogs would have to

be destroyed.† This decision was

indescribably painful for the men whose lives had depended upon these marvelous

animals.†††

When the Bear was

underway with all evacuees aboard, my father and Perce were happily surprised

to find that seven tiny puppies, just ten days old, had been smuggled aboard

the aircraft in duffel bags, inside jackets and anywhere else they could be

hidden.††

Ashley C. Snow, Jr. retired from the U.S. Navy after

thirty-two years of service.† He lived in

Pensacola, Florida, with his wife, Mildred, and his

three daughters, Ashley C. Snow III, Elizabeth Snow, and Laura Snow.† My father died on April 10, 1975, seven

months after the death of my mother.

Medals:

†††† Antarctic Service Medal, Gold

†††††††††††††††††††† Distinguished Flying Cross

Geographical

feature: Snow Nunataks

Contributions:††† Chief Pilot, East Base; Chief of Staff of Enlisted

Personnel; evacuation of East Base personnel

Photos

Films/Videos:

Full

Photo/Films/Video Library:

Links:††† Earle Perce, Biography